How not to invest

The Swiss National Bank has been getting a lot of flak for the large losses of last year. A recent article mentions the famous FX move of January 2015, but also reveals some interesting details of the SNB’s lack of success in the equity markets.

National banks and political leaders have a long and colourful history of getting it wrong. Of course there are many in the corridors of power who get it right – after all, most central banks make a steady profit year after year (from seigniorage, banking sector reserve requirements, and yes, sometimes even from the trading of currencies). But the financial markets have always enjoyed a regular dose of schadenfreude and the disasters are recounted much more often than the successes.

Gordon Brown spent over 10 years in the job of finance minister of the UK, made all manner of decisions and changes during his tenure. But the decision remembered most keenly by the financial markets was the sell over half the nation’s gold reserves at the lows between 1999-2002. A terrible trade to be sure, but only one of many – previous UK governments had sold off even more gold at even worse rates in the 60s and 70s. And the UK wasn’t alone in this error – Switzerland, Belgium and the Netherlands were all selling alongside. There were also plenty of central banks got it wrong at the highs as well. The Bank of Korea in particular appears to have a knack of only buying gold when it’s close to the highs.

A special place in the history of awful speculation is held by Bank Negara Malaysia (and the men who controlled the wizard from behind the curtain). An ill-fated effort to corner the tin futures market in 1981-82 ended with huge losses, and Malaysia fell from being the world’s biggest tin exporter to being a tin industry on the brink of collapse. This was followed by some serious losses on a long USD position, after the Plaza accord of 1985 reversed the strength of the greenback. Unperturbed, BNM went on to become the largest FX speculator in the world in the last 80s and early 90s, an episode which ended only when they bet the house against George Soros and lost $6 billion on being long the GBP and other currencies during the ERM exit of 1992. Unusually for a central bank, the BNM was effectively bankrupted by the losses and had to be recapitalised by the government. Not unusually, the responsibility was placed elsewhere – international currency speculators were to blame for the losses (according the world’s largest international currency speculator).

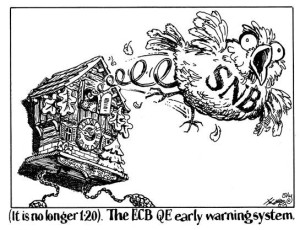

So in a historical context the SNB is not the first, not will it be the last central bank to lose money. What is quite astonishing in this story is not some ill-disciplined trading in the stock markets. It’s the fact that the SNB was unable to prevent a strengthening of their own currency in January 2015.

Preventing a weakening currency can sometimes be difficult – when reserves run low and there is no appetite for higher interest rates because of recession, a central bank trying to support its currency is in a very difficult position. But when a currency is strong, the chief danger of intervention to weaken it is that the increase in money supply can cause inflation, but there was precious little of that in Switzerland last year.

In the unflooring of January 2015, it’s almost as if the SNB was holding not just all of the aces but all of the picture cards as well, and still managed to lose the hand in an explosive and spectacular fashion.

Receive updates by email

Headline

Text body

Receive updates by email

On Bubbles and Bitcoin

/0 Comments/in blog, Finance and economics, Financial Markets, Investing /by Andy+China’s Balancing Act

/0 Comments/in blog, Economics, Uncategorized /by Andy+FAANGs for the Memories

/0 Comments/in blog, Financial Markets /by Andy+