receive updates by email

We learn from history that we learn nothing from history

“We learn from history that we learn nothing from history” according to the great philosopher of history, Georg Hegel.

The history of finance is no different. One of the most striking cycles that repeats itself over and over is the habit of people to borrow plentifully and cheaply during the good times, only to discover that they cannot pay back their debts when the good times inevitably end. History is littered with the same story over and over again.

During the recovery from the 2001 recession, the Fed kept rates at historically low rates for a historically low time, and even in 2004 when the hiking cycle started, monetary policy was kept very much on the accommodative side. For years, money was lent too cheaply and too enthusiastically and it was only in 2006 when rates finally normalised, that we found that it was American home-owners who had borrowed (or were lent) more than was sensible. In the aftermath of that crisis, we discovered that there were governments in the eurozone who had been given the opportunity to borrow at cheaper-than-historical rates from 1999 to 2010, and had taken ample opportunity to drink from the cup while it was full. Of course, when the liquidity tide turns the other way, as it did in 2010-2012, acceptable levels of borrowing become unacceptable very quickly.

The US recession previous to those events also led to significantly lower US interest rates (from 1992-93), and on that occasion it was enthusiasm for the Asian tiger miracle which caught the eye of international money-lenders. Many countries in Asia found it easy to borrow in the hubris, borrowed too much and when the enthusiasm died down, experienced the debt and currency crashes of the Asian crisis in 1996-97.

During the 70s, it was the commodity exporters of Latin America who were the darlings of the market. Anyone who exported oil and other commodities found it very easy to borrow money during the times of huge increases in the oil price that we saw from 1973-80. However the combination of Volker’s inflation-busting polices and the eventual fall in commodity prices in the early 80s proved devastating. All the big LatAm countries saw some combination of default, currency crash and hyperinflation in the early to mid-80s.

These episodes are still in the minds and in some cases the experience of people in the markets today, but they themselves were echos of previous even more ancient cycles. It is sometimes forgotten today, but Newfoundland was for 79 years a self-governing country, before losing its independence due to a debt crisis. During the roaring 20s when lenders were bullish, the country borrowed heavily to finance railway construction. However the 1929 crash and following depression sent commodity prices falling, and Newfoundland’s main export – fish – saw prices collapse along with everything else. An over-indebted commodity exporter is always going to have a tough time during a commodity price crash, but for Newfoundland the consequences were worse than for most. The country effectively handed rule back to London in 1934 and then was absorbed into Canada in 1949, never to run its own affairs again.

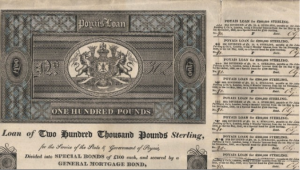

Perhaps the most bizarre case of over-enthusiastic lending was the incident of the Poyais government bond market back in the 1820s. The Napoleonic wars finally ended in 1815, and the years after saw high demand for commodities as Europe rebuilt and the manufacturing sector boomed. The newly independent countries of Latin America were rich in commodities and were a great attraction for international investors of the time. UK government bond yields fell to 3% as government finances recovered after the end of the war, however, the emerging LatAm countries were issuing bonds yielding around 6% in 1822 and carry hungry investors piled in. Enthusiasm was so high that a Scotish con-man called Gregor MacGregor issued £200,000 (which was a good sum in those days) of government bonds for a made-up central American country called Poyais. London investors bought up the lot at the same yields that Colombia and Peru had paid earlier in the year. Not for the last time, investors lent far too much money in good economic times with a lack of due diligence which was astonishing even by the standards of the times. Needless to say, the investment didn’t go well. Poyais bonds collapsed in London in 1823 and a new bond to be launched in Paris was scrapped in 1825 due to worsening market conditions. That particular economic cycle came to and end when the BoE hiked rates in 1825, which led to a series of bank failures in Europe and a global credit crunch. The calling in of loans and shortage of global liquidity led to sovereign defaults in Peru, Colombia and Chile in 1826, Brazil and Mexico in 1827, and Argentina in 1828.

Returning to the present day, we are at an historic juncture. US interest rates have been at rock-bottom levels for 7 years and the monetary accommodation in the major economies of the world has been at truly unprecedented levels, a happy situation that is coming to an end. Has someone lent – and someone else borrowed – money that will not be paid back when rates go higher?

If we learn one thing from financial history, it’s that some in finance have learnt nothing from financial history.